Maine Facts

Maine makes up one of the oldest American states. It was technically already around when the US declared its independence from Britain in 1774. While it is not one of the bigger states, Maine has played various important roles throughout American history. Even today, it still plays an important role in the US. Learn more with these 50 Maine facts.

- 01Maine covers an estimated area of 35,000 km².

- 02Water makes up an estimated 14% of the state.

- 03An estimated 1.34 million people live in the state.

- 04This gives the state an estimated population density of 17 people for every km².

- 05On average, a household in Maine makes an estimated $56,000 a year.

Several theories lie behind the state’s name.

The most plausible one involves the first French settlers naming the region after the former Maine Province in France. This stayed the case even after the English takeover, with the English government officially recognizing it as the region’s name in 1665. The modern state government also officially recognized this historical legacy in 2001, by setting May 6 as Franco-American Day.

That said, other theories exist as to the origin of the state’s name. One of them goes that Maine actually comes as a corrupted shorthand for the mainland, from when European explorers scouted out the coast in the past.

Another theory goes that Maine comes from the common Welsh place name, Mayne, usually those with rocky surroundings. Regardless of the various theories, scholars agree that as of today, no definite origin for the state’s name exists.

Various Native American tribes lived in Maine in the past.

The Red Paint People became the first to arrive in Maine, around 3000 BC. Their name comes from their elaborate burial grounds, and how they marked their dead with red ochre. Around 1000 BC, however, the Red Paint People disappeared, with the Susquehanna replacing them in Maine.

Over the following millennia, various Algonquian-speaking tribes would also settle in Maine. These included the Androscoggin, the Kennebec, the Maliseet, the Passamaquoddy, and the Penobscot. In the late-17th century, these tribes banded together to form the Wabanaki Confederacy. They also allied with the Wampanoags from Massachusetts, and the Mahicans from New York. Together, they fought a failed attempt to drive European colonists out of their lands.

The Norwegians became the first Europeans to visit Maine in the 13th century.

As Vikings, Norwegian explorers first discovered the New World in the 10th century, when they landed in what would become Newfoundland. From there, they explored the Atlantic coast of Canada and the Northeastern USA. They even tried to find settlements of their own but failed to do so.

Archaeological evidence suggested that they interacted with the natives, in particular, the Penobscot people. The evidence also suggests that trade flourished between the Vikings and the Native Americans. And unlike with later contact with the Europeans, relations between the Vikings and the natives proved much friendlier and more respectful of each other.

Maine struggled as part of Massachusetts in the 1800s.

The biggest reason for this involved the physical distance between Maine and Massachusetts. Specifically, the two regions had no actual land connection with each other, with New Hampshire sitting between them. This led to a perception in Maine that the Massachusetts state government had no vested interest in their wellbeing. This perception became reinforced by biased rulings on land issues in Massachusetts.

These issues led to a vote in 1807 in the Massachusetts Assembly, with the goal of breaking Maine off as a separate state or territory. The vote failed, and the issues became worse when in the War of 1812, pro-British leaders in Massachusetts practically abandoned Maine without a fight. A second vote in 1819 finally led to Maine becoming a separate US territory a year later in 1820.

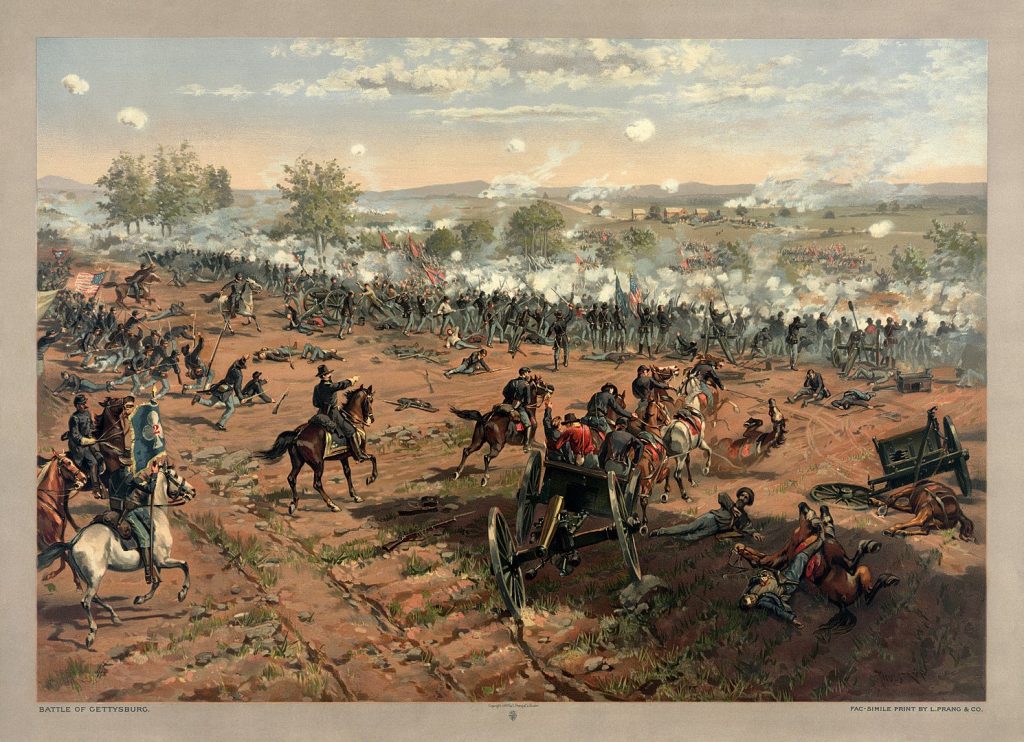

Maine became a state as part of the Missouri Compromise.

At the time, slavery played a major role in whether or not new states could join the Union. This came from the fact that whether or not slavery could stay legal depended on the state governments. Pro-slavery states maintained a balance in the US Congress, where the number of pro-slavery and anti-slavery states must remain equal. Maine counted among the latter, and this tangled up with them joining the Union as a state of their own.

In the end, this led to the Missouri Compromise, where the pro-slavery Missouri Territory also joined the Union as a state just like Maine did. This kept the balance in the US Congress, leading to no opposition for the new states joining as they did.